Galaxies via PCA and GP

Generating galaxies using PCA and Gaussian Process

Galaxies have a wide range of colors depending on the kinds of stars that make them up, the ages of those stars, and properties of dust in the interstellar space. And probably a bunch of other stuff too. However although there is technically an infinite possible number of galaxy spectra, there are not limitless possibilities since the distribution of emitted flux with wavelength depends upon a set of well-defined physical processes determined by star formation and atomic physics.

Given some galaxy color (ratio of its flux at adjacent wavelengths), we want to simulate its probable underlying galaxy spectrum, and one that is drawn from a continuous distribution. We need some way of defining this distribution such that it can produce any possible galaxy spectrum, but never an unphysical galaxy spectrum (i.e. one that cannot be produced by radiation from stars+dust).

We have an idea of what the range of galaxy spectra in the universe are like so we start from a set of discrete galaxy spectra we think (assume) roughly span the real range of galaxy spectra.

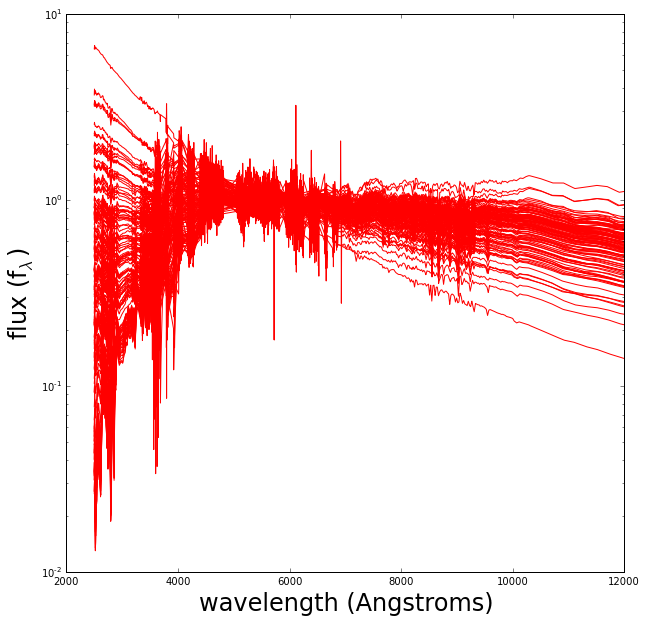

Plotted below is the set of discrete galaxy spectra I will use.

In [23]:

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA as sklPCA

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import sedFilter

import photometry as phot

import sedMapper

### Read the spectra into a python dictionary

listOfSpectra = 'brown_masked.seds'

pathToSpectra = '/mnt/drive2/repos/PhotoZDC1/sed_data/'

sedDict = sedFilter.createSedDict(listOfSpectra, pathToSpectra)

nSpectra = len(sedDict)

print "Number of spectra =", nSpectra

### Plot all together

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

sedFilter.plotSedFilter(sedDict, ax)Adding SED Arp_118_spec to dictionary

Adding SED Arp_256_N_spec to dictionary

Adding SED Arp_256_S_spec to dictionary

Adding SED CGCG_049-057_spec to dictionary

.....

Adding SED UGCA_219_spec to dictionary

Adding SED UGCA_410_spec to dictionary

Adding SED UM_461_spec to dictionary

Number of spectra = 129

Each one of these discrete spectra has colors associated with it (color is the ratio of integrated flux within two neighboring wavelength regions). Given any “real” set of galaxy colors we want to produce a likely underlying spectrum.

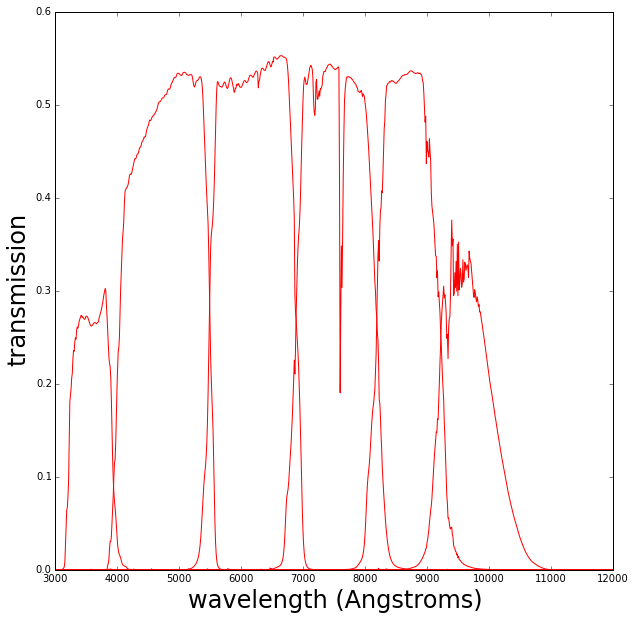

The color is estimated from the flux within a series of filters that define the wavelength regions (for this case these are plotted below).

In [24]:

### Filter set to calculate colors

listOfFilters = 'LSST.filters'

pathToFilters = '/mnt/drive2/repos/PhotoZDC1/filter_data/'

filterList = sedFilter.getFilterList(listOfFilters, pathToFilters)

filterDict = sedFilter.createFilterDict(listOfFilters, pathToFilters)

nFilters = len(filterList)

print "Number of filters =", nFilters

### Plot all together

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

sedFilter.plotSedFilter(filterDict, ax, isSED=False)Adding filter LSST_u to dictionary

Adding filter LSST_g to dictionary

Adding filter LSST_r to dictionary

Adding filter LSST_i to dictionary

Adding filter LSST_z to dictionary

Adding filter LSST_y to dictionary

Number of filters = 6

We want to define a relationship between the “observable”, the galaxy colors, and the spectrum we wish to predict.

It is a natural choice to decompose the spectra into a representative basis of “eigenspectra” using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This is because in the simplest sense a galaxy spectrum is just a sum of different spectra of stars. The distribution of galaxy spectra could be then defined by the distribution of eigenvalue sets corresponding to the different eigenspectra, as derived from our set of discrete spectra.

We then need to make a mapping between color and a particular set of eigenvalues in order to reconstruct a galaxy spectrum given any set of galaxy colors. We don’t know what functional form this mapping relationship might take, and ideally we don’t want to restrict any model options, or be too flexible and allow for over-fitting that would render the derived mapping useless for any galaxies not within the original discrete set of spectra.

The Gaussian Process is a Bayesian method that assigns a set of prior probabilities to every possible function (e.g. higher probabilities to smooth functions, Occam’s razor) that could explain some observed data. The problem becomes tractable because you require estimates of the functional form only at particular points in the variable space (in this case galaxy colors). Once the prior probabilities for the set of functions are confronted with data points, their combination leads to a posterior distribution for the functions. It is the statistical properties of the resulting posterior distribution that supply the inference of the output (here eigenvalue set) given new input variables (here galaxy colors).

A covariance function used in the Gaussian Process decides the form the prior probabilities will take, by defining the shape of the prior probability distribution, and having a characteristic length scale to control quickly the prior probability changes over the function space. The covariance function is a function of the input variables. I think this is what makes the problem tractable, because the computation required is just the inversion of a matrix that is the size of the dimensionality of the data set.

The use of this method is not my idea and an original implementation can be found here.

In [25]:

### Wavelength grid to do PCA on

minWavelen = 2999.

maxWavelen = 12000.

nWavelen = 10000

### Calculate all spectra colors, do PCA and train GP

ncomp = nSpectra # keep all components for now

# pre-calculated colors for these spectra

color_file = "brown_colors_lsst.txt"

# parameters for Gaussian Process covariance function

corr_type = 'cubic'

theta0 = 0.2

pcaGP = sedMapper.PcaGaussianProc(sedDict, filterDict, color_file, ncomp,

minWavelen, maxWavelen, nWavelen,

corr_type, theta0)

colors = pcaGP._colors

spectra = pcaGP._spectra

waveLen = pcaGP._waveLen # wavelength grid

meanSpectrum = pcaGP.meanSpec # mean spectrum

eigenvalues = pcaGP.eigenvalue_coeffs # eigenvalues for each spectrumColors already computed, placing SEDs in array ...

On SED 1 of 129 NGC_4254_spec

On SED 2 of 129 NGC_6240_spec

On SED 3 of 129 UGC_06850_spec

.....

On SED 127 of 129 NGC_1144_spec

On SED 128 of 129 NGC_1068_spec

On SED 129 of 129 NGC_2623_spec

Mean spectrum shape: (10000,)

Eigenspectra shape: (129, 10000)

Eigenvalues shape: (129, 129)

Number of unique colors in SED set 129 total number of SEDs = 129

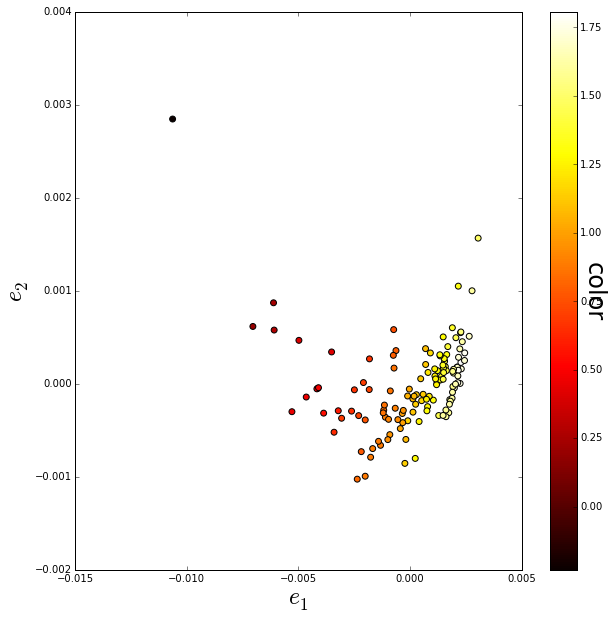

Plotting the first two eigenvalues shows that eigenvalue 1 gives a strong indication of galaxy color. A galaxy is “redder” if the “color” value is larger, and “bluer” if the value is smaller.

Very roughly a “blue” galaxy is star-forming and a “red” is old and no longer forming stars.

In [26]:

# plot distribution of first two eigenvalues

cm = plt.cm.get_cmap('hot')

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

cb = ax.scatter(eigenvalues[:,0], eigenvalues[:,1], c=colors[:,0], s=35, cmap=cm)

ax.set_xlabel('$e_1$', fontsize=24)

ax.set_ylabel('$e_2$', fontsize=24)

cbar = plt.colorbar(cb)

cbar.set_label('color', rotation=270, fontsize=24)

ax.set_xlim([-0.015, 0.005])

ax.set_ylim([-0.002, 0.004])

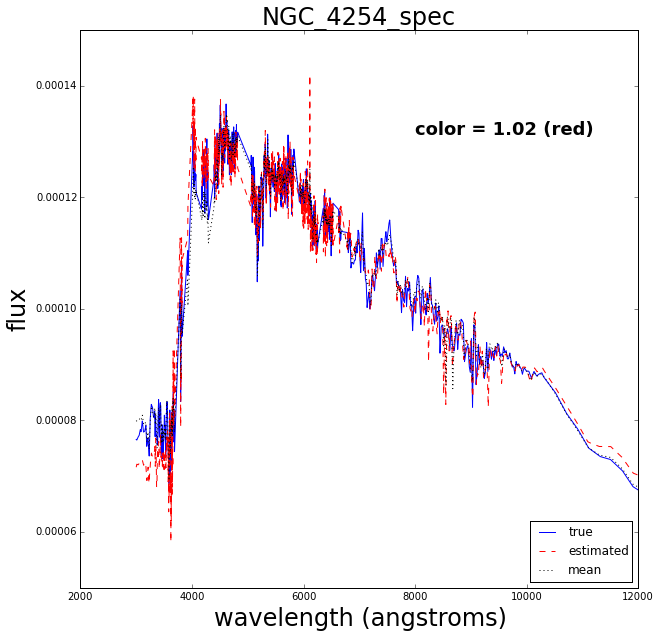

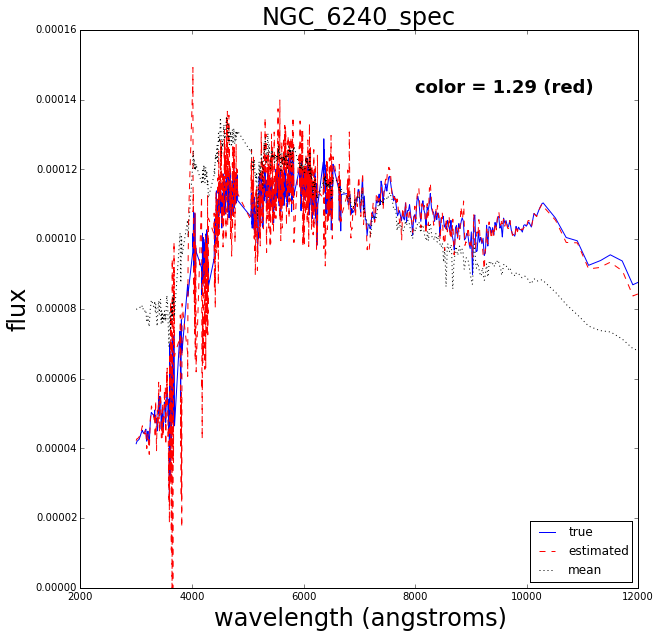

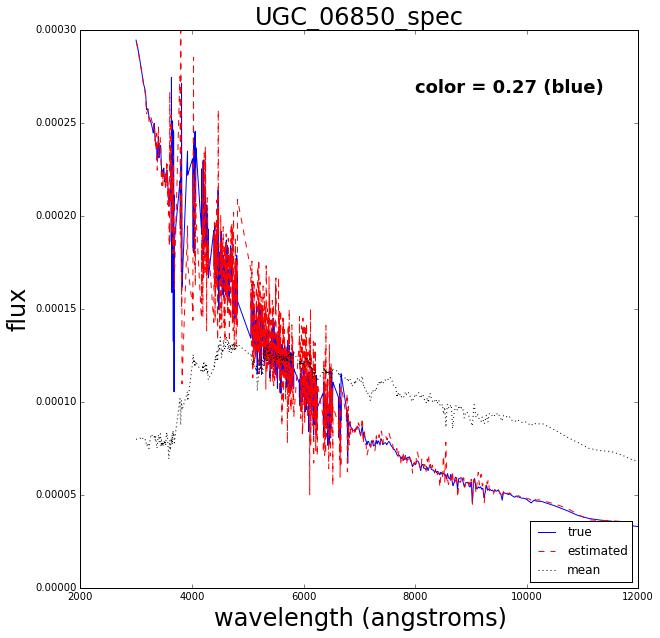

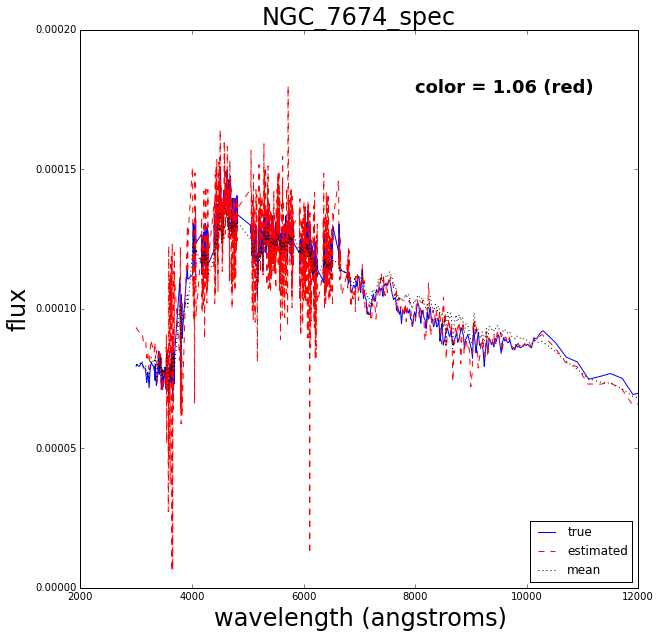

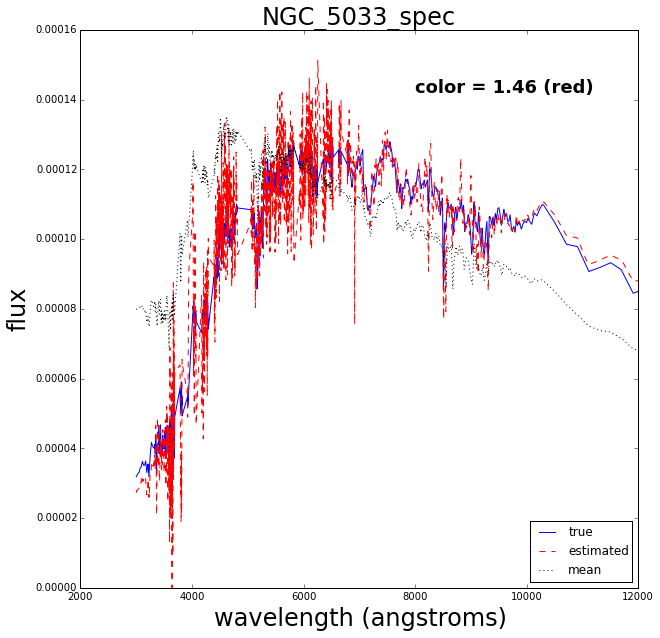

Now let’s do a test where we retrain the Gaussian process after removing one of the spectra, then try to see how well it reconstructs the missing spectrum.

In [27]:

### Leave out each SED in turn

delta_mag = np.zeros((nSpectra, nFilters))

performance = []

for i, (sedname, spec) in enumerate(sedDict.items()):

print "\nOn SED", i+1 ,"of", nSpectra

### Retrain GP with SED removed

nc = nSpectra-1

pcaGP.reTrainGP(nc, i)

### Reconstruct SED

sed_rec = pcaGP.generateSpectrum(colors[i,:])

### Calculate colors of reconstructed SED

pcalcs = phot.PhotCalcs(sed_rec, filterDict)

### Get array version of SED back

wl, spec_rec = sed_rec.getSedData(minWavelen, maxWavelen, nWavelen)

### Plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10,10))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(waveLen, spectra[i,:], color='blue', label='true')

ax.plot(wl, spec_rec, color='red', linestyle='dashed', label='estimated')

ax.plot(waveLen, meanSpectrum, color='black', linestyle='dotted', label='mean')

ax.set_xlabel('wavelength (angstroms)', fontsize=24)

ax.set_ylabel('flux', fontsize=24)

handles, labels = ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

ax.legend(loc='lower right', prop={'size':12})

ax.set_title(sedname, fontsize=24)

y1, y2 = ax.get_ylim()

typeg = 'red'

if (colors[i,0]<0.5):

typeg = 'blue'

annotate = "color = {0:.2f} ({1:s})\n".format(colors[i,0],typeg)

ax.text(8000, 0.85*y2, annotate, fontsize=18, fontweight='bold')

### Break after 4

if (i>3):

breakOn SED 1 of 129

Mean spectrum shape: (10000,)

Eigenspectra shape: (128, 10000)

Eigenvalues shape: (128, 128)

Number of unique colors in SED set 128 total number of SEDs = 128

On SED 2 of 129

Mean spectrum shape: (10000,)

Eigenspectra shape: (128, 10000)

Eigenvalues shape: (128, 128)

Number of unique colors in SED set 128 total number of SEDs = 128

On SED 3 of 129

Mean spectrum shape: (10000,)

Eigenspectra shape: (128, 10000)

Eigenvalues shape: (128, 128)

Number of unique colors in SED set 128 total number of SEDs = 128

On SED 4 of 129

Mean spectrum shape: (10000,)

Eigenspectra shape: (128, 10000)

Eigenvalues shape: (128, 128)

Number of unique colors in SED set 128 total number of SEDs = 128

On SED 5 of 129

Mean spectrum shape: (10000,)

Eigenspectra shape: (128, 10000)

Eigenvalues shape: (128, 128)

Number of unique colors in SED set 128 total number of SEDs = 128

The blue solid line is the true spectrum, the dashed red is the reconstructed spectrum and the dotted mean is the mean over the 129 spectra.

The reconstruction works pretty well.